In November, Telegram and Europol launched a two-day coordinated campaign focused on removing Islamic State (IS) channels, groups, and pro-Islamic State accounts from the platform. Although Telegram had made previous efforts to take down IS content, the November campaign was far greater in scope. A Europol official discussed the process of tracking Islamic State supporters’ online activities in an interview conducted by researcher Amarnath Amarasingam: “We started flagging terrorist content to Telegram, and gradually we established a channel of communication and cooperation with Telegram…We cover a large number of online service providers, not just Telegram. But at some point last year, we took time to specifically look at Telegram. We did a joint action…we knew that if this went well, it would shake up the community of jihadist propagandist on Telegram.”

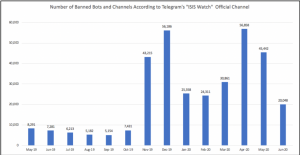

The efforts to disrupt IS networks are reflected by Telegram’s “ISIS Watch,” an official channel that “publishes daily updates on banned terrorist content”:

Screenshot of “ISIS Watch’s” official channel information page

A bar graph reflecting the number of banned bots and channels according to “ISIS Watch”

Nearly half a year has passed since the November 2019 campaign and Telegram has maintained continuous pressure on IS, but Islamic State supporters have managed to maintain their presence on the platform. This insight will highlight several perspectives on the anti-IS Telegram campaign and offer policy suggestions on how to better balance the diverse set of objectives that various parties (researchers, practitioners, online IS hunters, and law enforcement) are trying to accomplish.

Perspectives: Researchers, Online IS Hunters, and IS supporters

A Europol report titled “Online Jihadist Propaganda: 2019 in Review”, recently released on 28 July 2020, shared key findings about the Telegram campaign:

- The takedown action coordinated by EU Member States and Europol on 21 -22 November resulted in an extensive eradication of pro-IS accounts, channels and groups from Telegram

- Official as well as supportive IS media outlets and groups are still struggling to rebuild their networks online, with efforts continuing across several platforms

The report went on to state that “IS supporters’ subsequent attempts to regenerate their networks via the creation of new groups and channels were unsuccessful…” and pro-IS networks shared “guidance on which platforms could provide more safety to IS supporters following the loss of Telegram.” Although IS supporters have struggled to remain on Telegram to a certain degree, they have, nonetheless, managed to maintain an active presence on the app where media dissemination of both official and unofficial propaganda continues at a steady pace. Describing it as a “loss of Telegram” somewhat mischaracterises the reality of the situation. However, this leads to another set of questions: What does success look like? Can various objectives even conflict with one another? Do Telegram disruption campaigns contribute to reaching the intended goals?

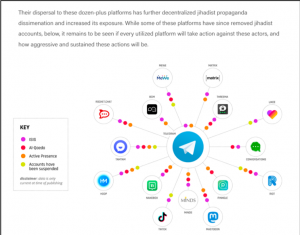

Some researchers have made the important point that “the harder it is for us [researchers] to find terrorist hangouts, the harder it is for prospective recruits” but others have discussed the possible dangers of further decentralisation – including making it more difficult for “authorities to monitor terrorist activity.”

Ayse Lokmanoglu, a PhD candidate at Georgia State University who has monitored IS Telegram for three years, said about the campaign, “The Telegram take down had a momentary impact on IS, but they very quickly reorganised and backed up their communications on other platforms. Mass censorships and takedowns are rarely effective in the contemporary environment; as technological adoption no longer requires much tech skills. Empirically, they also continued their release of al-Naba and official news announcements and videos. So in essence, it had a limited effect on their official media campaign.”

A report from Flashpoint provides a visual for this process of further decentralisation that Lokmanoglu described:

Although many researchers were ultimately able to have their observation accounts reinstated, account deletions have proven to remain a continuous issue for online IS hunters, creating a potentially serious blind spot. Unlike researchers, many IS hunters work anonymously and do not have a method of institutional verification to protect their tracking accounts from bans. I asked a French and a North American online IS hunter for their thoughts on the Telegram campaign and how it has affected their work:

“At the time, the series of suspensions created a stir among IS supporters but unfortunately, they quickly tried to migrate to other platforms and encrypted messaging apps. Additionally, the deletions of accounts and groups had consequences for our own infiltration accounts. They were all deleted; one right after another along with the months of work that went into them. We can see that terrorist propaganda is still there – one of the most astonishing examples being Daeshi female prisoners in Al Hol camp with their own channels and ability to continue quietly communicating [on Telegram]. The second issue is that the Telegram campaign had catastrophic consequences for our hunting activities. Our accounts were suspended because they were mistaken for being a part of the “propaganda chain” just like actual pro-Daesh accounts. A whitelist doesn’t exist where we can safelist our accounts with Telegram.” – French Online IS hunter who goes by “Nath”

“It has definitely slowed down the IS propaganda machine on Telegram, but it has completely blinded us. We lost six months to a year’s worth of work. I understand their [Telegram’s] efforts but they’re hurting potential law enforcement investigations and we have lost high-value targets.” – North American IS hunter

In terms of Islamic State media responses, a 28 November 2019 al-Naba release, translated by researcher, Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi, asserted: “And likewise their efforts to restrict the activities of the ansar [supporters] who expend great effort in publishing the media items of the mujahideen through different means have failed. And the most important among them is the wide complex Internet network. That is because of their abundance in number…. which makes the mission of undertaking a broad campaign against them entirely nearer to impossible for them…”

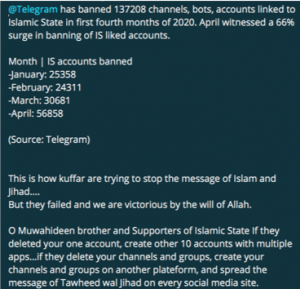

Islamic State supporters, on the other hand, have expressed both frustration with the bans and a sense of victory over these efforts to remove them from the platform. They have also attempted to discover ways to defeat the bans through trial and error methods and they continue to promote alternative platforms:

Screenshot from a pro-IS Telegram group, May 2020

On an additional note, it is worth mentioning and further examining Telegram’s policy regarding white nationalist content in comparison to how it has handled content from IS and al-Qaeda media outlets and supporters. Telegram has become increasingly popular for white nationalists who have utilised this platform in ways that parallel Islamic State supporters’ usage of the app. During my own observation of white nationalist Telegram groups, they have, on numerous occasions, shared bomb-making instructions which included an IS instructional video on how to produce TATP. In a statement to CNN, Telegram said, “While we do block terrorist bots and channels, we will not block anybody who peacefully expresses alternative opinions…our mission is to support privacy, free speech and peaceful exchange of ideas.” The sharing of bomb instructions does not fall under a freedom of speech policy and this is an inconsistency that must be resolved.

Conclusion and Policy Suggestions:

Finding ways to balance effectively disrupting Islamic State supporters’ online activities without keeping researchers and IS hunters “in the dark about the activities of the likes of the Islamic State” is no easy task, but a more nuanced approach could have a stronger impact. The following are some possible suggestions but with the important caveat that it is impossible to have a complete picture of confidential behind-the-scenes policies and methods that Telegram enacts or its exact relationship with law enforcement agencies which may vary from country to country:

• Provide a method of verification and/or line of communication for IS hunters, who frequently operate under pseudonyms, to whitelist their accounts in order to allow tracking efforts to continue uninterrupted. However, that being said, this would not be a simple task due the importance of verifying that an individual is legitimate and such an approach would need to be discussed more in-depth. A proposed solution could be maintaining contact with a researcher who can verify themselves and then, in turn, working with these verified researchers to whitelist hunters while maintaining the degree of anonymity that many hunters operate under.

• Utilise various metrics and goals to define what success means and balance these needs accordingly while keeping in mind that some objectives may overlap while others may even conflict. For example, one goal might include making it more difficult for prospective recruits to find entry points into online IS echo-chambers while another objective might be more intel-driven. Heavy deletions are necessary to cut off access points but, as discussed by the online IS hunters, this conflicts with their intel-driven infiltration operations. A possible solution that balances both of these concerns could entail banning any groups, channels, or bots that are discoverable through a generic key word search while allowing selected private groups and channels to remain up in order to avoid disrupting intel gathering and tracking efforts.

• Cut off access to all public channels and groups that can be found on Telegram through a generic keyword search.

• Work with other platforms to coordinate future initiatives.

• Find ways to implement consistent policies when dealing with violent extremist groups or accounts; regardless of their ideology.