The previous post on Eulogius' defence of the martyrs of Córdoba included an early Latin biography of the Prophet Muhammad. The biography was extremely disparaging in tone, accusing Muhammad of being driven by Satan and excess libido, while commanding his followers to butcher their opponents. At the same time, the biography does capture some concrete details about Muhammad's life that coincide with the traditional Islamic accounts, such as the appearance of the angel Gabriel to him, the composition of suras of the Qur'an and Muhammad's marriage to Zaynab bint Jahsh (who had been the wife of Zayd bin Haritha).

In sharp contrast, we have another early Latin biography of Muhammad that presents a very different story. This biography, whose precise origin is highly obscure but is found in a manuscript from Spain, presents Muhammad as originally having been a monk called Ozim/Ocim attached to the bishop Osius: another name of the bishop Hosius of Córdoba, who lived in the third and fourth centuries. For much of his life, Hosius had been distinguished as a defender of orthodoxy, but towards the end of his life he was one of the authors of a declaration at Sirmium (located in modern-day northern Serbia) that is condemned for affirming Arian ideas about the relationship between the Father and Son in Christian doctrine. The text of the declaration can be found in chapter 11 of Hilary of Poitiers' work De Synodis. The relevant excerpts read as follows:

unum constat Deum esse omnipotentem et patrem, sicut per universum orbem creditur: et unicum filium eius Jesum Christum Dominum salvatorem nostrum, ex ipso ante saecula gentium...scire autem manifestum est solum Patrem quomodo genuerit filium suum, et Filium quomodo genitus sit a Patre. nulla ambiguitas est maiorem esse Patrem. nulli potest dubium esse Patrem honore, dignitate, claritate, maiestate, et ipso nomine patris maiorem esse Filio, ipso testante: qui me misit, maior me est.

'It is agreed that there is one omnipotent God and father, as is believed through the whole world: and His only son is Jesus Christ the Lord our saviour, born from Him before time...but it is clear that the Father alone knows how He begot His Son, and the Son how He was begotten by the Father. There is no ambiguity that the Father is greater. It cannot be doubted by anyone that the Father in honour, dignity, clarity, majesty, and in the very name of father is greater than the Son, who himself bears witness: He who sent me, is greater than I.'

For context, this idea of the relationship between the Father and Son (i.e. that the Son is subordinate to the Father) goes contrary to the mainstream understandings of Christianity that exist today and posit the Son and Father as equal in status.

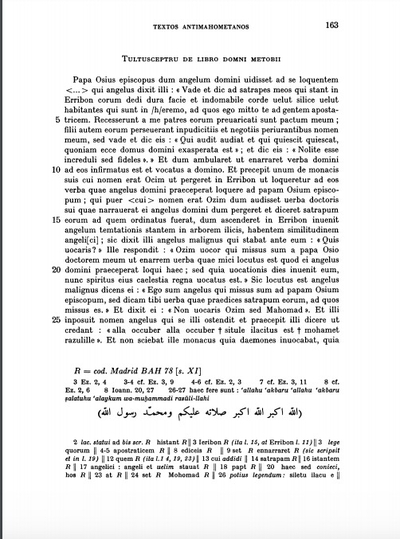

However, this Latin biography of Muhammad does not mention Hosius' apparent lapse into Arian ideas but portrays him as someone who was called into the kingdom of heaven on his death. According to the biography, Hosius had originally been instructed to preach the words of the Lord to the Arabs, who are presented as an 'apostate' people whose ancestors had deviated. However, on account of weakness and his imminent death, Hosius instead entrusted the preaching to the monk Ozim, who headed towards the place called Erribon (identified as Yathrib, the original name for the town of al-Medina prior to Muhammad's arrival). On his way though, Ozim encountered the devil disguised in the form of an angel. The devil claimed to be the same angel who appeared to Hosius and instructs him to call himself Muhammad, and preach the following call, which is a partial and somewhat mangled Latin transcription of the Islamic call to prayer:

Alla occuber Alla occuber situle ilacitus est Mohamet razulille

The first four words and the last two words are evident: they are renderings of الله اكبر (Allahu Akbar: 'God is greatest') and محمد رسول الله (Muhammad Rasul Allah: 'Muhammad is the Messenger of God') respectively. The three words in the middle have been variously interpreted. In an article by Diaz y Diaz that edited the original Latin text, situle ilacitus est is interpreted in a footnote as صلاته عليكم (salatuhu alaykum), which can be translated as 'His prayer be upon you' (i.e. God's blessings be upon you). Diaz y Diaz also has a suggested correction of the Latin transcription to siletu ilacu e. Robert Hoyland, cited in Kenneth Baxter Wolf's paper on the early Latin biographies of Muhammad, renders it as أشهد ان لا إله الا الله (ashhadu anna la ilah ill Allah- 'I bear witness that there is no deity but God'). I find this latter reading to be more plausible as it was what it sounded like to me as I read it. I would render the entire phrase from situle to razulille as a somewhat mangled rendering of the declaration of faith in the call to prayer: أشهد ان لا إله الا الله اشهد ان محمداً رسول الله (ashhadu anna la ilah ill Allah ashhadu anna Muhammadan rasul Allah- 'I bear witness that there is no deity but God, I bear witness that Muhammad is the Messenger of God'). Kenneth Baxter Wolf suggests that the middle three words sound more like Latin ('as if something was cited (citus est) in place of something else (situ)'), but I cannot think of a plausible rendering of the meaning in that case.

Whatever the case, the biography portrays the phrase taught to Muhammad by the devil as invocations of demons, which Muhammad repeats without realising their true significance. Thus, besides the divergence in actual biographical details, this biography contrasts with the one quoted in Eulogius' work in the way it understands Muhammad's motivations. Rather than depicting him as an evil heretic knowingly doing the devil's work, this biography portrays him as being unknowingly duped by the devil. While the end result is the same (i.e. his followers end up in hellfire), this biography does not approach the harshness of the one that is contained in Eulogius' work and says that the mangling of Muhammad's corpse by dogs was a just end for him.

In general, the Latin in this text is far removed from the refined classical Latin and even appears to contain grammatical errors. Diaz y Diaz dated the insertion of the text into a manuscript at some point between 1030 and 1060 and commented as follows on the text in general:

'The text that is offered to us in the supposed extract of Metobius is incorrect, plagued by incongruities and also full of small lacunae, as if the copyist were taking laboriously his materials from a marginal fragment or a not very clear little note. I think, moreover, that he was copying from a manuscript that he did not always understand well, and this manuscript might have been in non-Visigothic lettering.'

I would like to dedicate this work to Jasmine El-Gamal, an Egyptian-American friend of mine who has been very supportive of my work and has similarly been interested in Western perceptions of Islam and Muslims. May you prosper as you move into the next stage of your life, my friend.

The Latin text followed in my translation below is that given in the article of Diaz y Diaz. I include some notes for context.

Tultusceptru[i] from the Book of Lord Metobius[ii]

Father Osius the bishop, when he had seen[iii] the angel of the Lord speaking to him...[iv]this angel said to him: 'Go and speak to my satraps[v] who are[vi] in Erribon, I have endowed this band of people[vii] with hard face and indomitable[viii] heart like flint, as they are inhabitants who are in the desert. I send you to them as they are an apostate people. Their fathers receded from Me and violated My pact, while their sons continue with shameless conduct and business committing perjury against My name.[ix] But go and say to them: 'He who hears, let him hear.[x] And he who is quiet, let him be quiet, because behold the house of the Lord has become exasperated.' And say to them: 'Do not be incredulous but believers."[xi]

And while he was travelling in order to narrate the words of the Lord to them, he became weakened and was called by the Lord. And he ordered one of his monks who was called Ocim[xii] to go into Erribon and speak to them the words which the angel of the Lord had entrusted to father Osius the bishop to say.[xiii] This youth whose name was Ozim heard the words of his teacher which the angel of the Lord had narrated to him. As he was going to speak to the satraps of those to whom he had been ordained,[xiv] and as he was ascending into Erribon, he found the angel of temptation[xv] in an oak tree,[xvi] having the similitude of the angel.[xvii] Thus the evil angel who stood before him said to him: 'What is your name?' He responded: 'My name is Ozim. I have been sent by father Osius my teacher in order to narrate the words he told me because the angel of the Lord had ordered him to speak these things. But as the day of calling found him, now his spirit has been called to the heavenly kingdoms.' Thus the evil angel spoke saying to him: 'I am the angel who was sent to father Osius the bishop, but I will tell you the words which you will preach to the satraps[xviii] of those people, to whom you have been sent.' And he said to him: 'Your name is not Ozim but Mohamad.' And this name was imposed on him by the angel, who showed himself to him and ordered him to say so that they should believe: 'Alla occuber Alla occuber situle ilacitus est Mohamet razulille.'

And that monk did not know that he was invoking demons, that every 'Alla occuber' is summoning of demons,[xix] that already his heart had been corrupted[xx] by an impure spirit and the words which the Lord had narrated to him through his teacher had been handed over to oblivion.[xxi] And what was previously the vessel of Christ was made into a vessel of Mammon through the perdition of his soul. So both all who have been converted in this error and those who have persuaded with his persuasion are reckoned to be of the maniples of hellfire.[xxii]

[i] Possibly a corrupt form of tultum excerptum ('extract taken from...'): Vázquez de Parga cited in Wolf.

[ii] Possibly a corruption of Metodius (Wolf).

[iii] The construction here is dum with the pluperfect subjunctive. The usual construction in classical Latin is cum with the pluperfect subjunctive.

[iv] Lacuna in the original text.

[v] Latin: satrapes (plural of satraps, a third declension noun). The word originally meant an ancient Persian provincial governor. Here it is probably generalised to rulers of eastern realms.

[vi] Latin: stant. The original meaning of the verb is 'stand' but here it reflects what is a precursor to the use of Romance descendants of this verb to mean 'be' in the sense of 'be located' (cf. Spanish: estar).

[vii] Latin: corum, likely from chorus, which can mean a general group or troop of people beyond its original Greek meaning.

[viii] Latin: indomabile. The more usual ablative ending in this case is in -i. The construction in this phrase seems to be dare in the sense of 'endow' with the accusative of recipient and ablative of the thing endowed.

[ix] The Diaz y Diaz article notes parallels with the Book of Ezekiel (2:4), in which God describes Israel's transgression against the Lord, conduct continued by the children of the fathers who have rebelled against God. The comparison of something in hardness to flint is also in Ezekiel (3:9), though in that book it is applied to the strengthening of the prophet's forehead by God so he need not fear the rebellious people of Israel, whereas here it is seems to be applied to attributes granted to the Arabs.

Wolf comments: 'It is unusual to find the pre-Islamic Arabs described as apostates as opposed to pagans. This would seem to have a lot to do with the author's decision to tap into Ezechiel's mission to the wayward Israelites.' One way to interpret the description of the Arabs as apostates is to posit that they traditionally worshipped a deity in some kind of monotheistic setting but over time they incorporated idols into their religion on the basis that they were intermediaries to get closer to the supreme deity. Interestingly this idea has parallels in Islamic discourse that claims the Arabs worshipped God (Allah) prior to Muhammad's mission but thought the idol deities were ways to get closer to God. For example note this explanation on the site Islamqa:

'You must know that the Arab societies before Islam were not atheist societies denying the existence of God [Allah] or societies ignorant of the fact there is a sustaining creator lord, but rather they knew that, and there was among them remnants of the religion of Abraham, and their relation with the Jews and Christians was present, but their problem was they did not make God exclusive in worship alone without one besides Him, but rather they associated as partners with Him the gods that they worshipped, and they worshipped them not on the pretext that they are the sustaining creator Lord but rather they claimed that they are intermediaries between them and God, and their nearness to God. Therefore God said about them: 'And if you ask them who created them, they indeed say God.' So this shows they acknowledged that God is the creator, and in another verse the Exalted says: 'And if you ask them who created the Heavens and Earth, they indeed say God.' And likewise in many verses showing their faith in the oneness [tawheed] of lordship, but their idolatry was in divinity as the Exalted and Almighty said about them: 'And those who have taken those besides Him as helpers: we do not worship them except so that they should bring us closer to God in sycophancy.' That is, they say we do not worship them except so that they should bring us closer to God.'

It is possible the author had some vague idea about the claim that the Arabs had worshipped the one God originally but then deviated through incorporating other deities, though the author seems unaware of the identification of Allah with God.

[x] This phrase has more than one parallel in the Bible: e.g. Mark 4:9 and Matthew 13:9 ('he who has ears, let him hear').

[xi] Cf. John 20:27.

[xii] Two explanations of this name have been offered. One is to suggest that it is 'Hisham/Hashim' (Wolf) while another (Hoyland, cited in Wolf) is that it is a rendering of the Arabic word عظيم (azim- 'great'). When I read this text, the former explanation struck me as more plausible. After all, Hashim is the name of Muhammad's great-grandfather and the name of Muhammad's clan within the Quraysh (the Banu Hashim), according to Islamic tradition. I think the form 'Hisham' given in the footnote in Wolf's article is a typo and he meant just to say 'Hashim' as in the main text of his article.

[xiii] Latin: loquere. Intended as an infinitive form here, though given that the verb is deponent loqui is the usual infinitive form and it also appears in this text.

[xiv] Latin: dum pergeret et diceret satrapum eorum ad quem ordinatus fuerat. The phrasing here is awkward and seemingly ungrammatical. Clearly the sense is that Muhammad was to go and preach the message to the satraps but satrapum is the genitive plural form of the noun, whereas the verb dicere more usually takes the dative in the sense of speaking to someone (cf. elsewhere in the text). Wolf renders the phrase ad quem ordinatus fuerat as follows: 'what had been commanded.' In this reading quem is taken as standing for quod ('that which/what') with a masculine-neuter form blurring, while ad with accusative is taken to stand for the direct object with dicere. Another possible reading in my view is that this part of the phrase refers to Muhammad's assignment to the satraps by Hosius, and quem is a mistake in using the singular instead of plural quos. Ergo: 'to whom he had been ordained.'

[xv] i.e. Satan.

[xvi] Latin: stantem in arborem ilicis. In translation stantem can be omitted as it functions as a verb to indicate location (cf. comment earlier on stare as 'to be').

[xvii] i.e. The angel of the Lord.

[xviii] Latin: satrapum. Genitive plural form for what should be dative.

[xix] Wolf cites González Muñoz as noting that this statement is 'consistent with eastern Christian ideas about Islam, specifically the idea that 'Allah' and 'Akbar' represent two different deities.' I am not sure about this interpretation of the text here.

[xx] The Latin noun cor is taken as a masculine noun here though it is supposed to be neuter.

[xxi] Latin: verba quae ei dominus narraverat per doctorem suum oblivioni traditum fuerat. The last two words traditum fuerat should be tradita fuerant to concord with the neuter plural subject verba. Note that in Ancient Greek a neuter plural subject is usually taken with a singular verb (Abbott and Mansfield: Primer of Greek Grammar).

[xxii] Latin: unde et omnes in errore conversi sunt et eos qui persuasione suaserunt manipula incendii nuncupantur. This phrasing poses a couple of problems. It probably makes sense to insert qui between omnes and in (i.e. 'all who have been converted'). The form eos is accusative plural but is not the direct object of a verb. It seems to me that the author was confused in taking nuncupantur with accusative. The correct form should be ei. The phrase persuasione suaserunt should be taken as referring to those who have engaged in active promulgation of Muhammad's doctrine, set alongside those who have been converted in error. It should not be taken as a passive phrase referring to future time as Wolf suggests.