The Syrian government's recent recapture of the last rebel-held pocket in the vicinity of Mt. Hermon (Jabal al-Sheikh) near the border with the Golan Heights- comprising the three towns of Beit Jann, Mazra'at Beit Jann and Mughir al-Mir- has led to much exaggeration and distortion about the matter, primarily emanating from Israeli discourse and supporters of the rebels. Based on their narrative, one would think that the recapture of this rebel-held pocket was an operation led by Iran/Hezbollah, as part of a strategic goal of developing a front against Israel. In the days leading up to the recapture of the Beit Jann pocket, rebel supporters increasingly played up the idea of an Iranian/Hezbollah-directed operation, such as through using the hashtag #Iran_burns_Beit_Jann (ايران_تحرق_بيت_جن#).

Yet there is little evidence to support these claims. Many outsider observers who began promulgating these claims only seem to have begun following events in the area in the last several days, unaware that the campaign to regain control of this rebel-held pocket had been going on for some months. As a result, context for the operations within the history of the Syrian civil war has been lacking.

An examination of this context shows that the Syrian government itself has been the leading actor in the attempts to recover the Beit Jann pocket. The military operations came about because the Beit Jann pocket repeatedly rejected 'reconciliation' whereas neighbouring villages accepted it at the turn of 2017. The villages that accepted 'reconciliation' were Kafr Hawr, Beit Saber, Beit Tayma, Hasano and Sa'sa'. The mechanism of 'reconciliation' often eliminates the need for an all-out military assault as it formally brings an area back under government control, but it frequently relies on exerting leverage through government control of routes that are vital for commodities/goods to enter a town that is partly or fully under rebel control. In other words, the government may threaten or impose a partial or full siege. 'Reconciliation' normally involves the process of taswiyat al-wad' for rebels who agree to stay, as well as others wanted for obligatory and reserve service. This process allows for a temporary amnesty of some sort rather than a permanent exemption from military service.

Apart from this point, the terms of 'reconciliation' and the parties involved in the negotiations can vary from place to place. In 'reconciliation' in certain Deraa localities considered to be a wider model for the southern region, a key figure on the government side in the negotiations has been Wafiq Nasir, who is the military intelligence head for the southern region. Further, rebel factions have largely been left intact to manage internal security matters in the towns, though they do agree not to attack government and army positions.

In the villages neighbouring the Beit Jann pocket, the key person involved in the negotiations for 'reconciliation' was a female media activist/broadcaster called Kinana Hawija, the daughter of Syrian army officer Ibrahim Hawija. She also played a supervisory/leading role in negotiations over the south Damascus suburb of Darayya and the Damascus countryside locality of Khan al-Shih that lies alongside the Damascus-Quneitra highway. The other notable feature of the 'reconciliation' in the villages neighbouring the Beit Jann pocket was the establishment of a local holding force called the Hermon Regiment, largely composed of ex-rebel fighters and affiliated with the military intelligence but also funded by Rami Makhlouf's al-Bustan Association.

The Beit Jann pocket rejected 'reconciliation' and continued to do so for multiple reasons. For one thing, from the perspective of the fundamental cause of the 'revolution', accepting 'reconciliation' essentially amounts to surrender. Despite fact that the government won a strategic victory in the recapture of Aleppo city in December 2016, many rebels are not prepared to give up on their cause just yet. Indeed, the notion of refusing to give up and continuing the 'revolution' is one of the fundamental premises of the jihadist Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, a successor to Jabhat al-Nusra, which was once Syria's al-Qa'ida affiliate. The Beit Jann pocket had a substantial presence of Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham, unlike the neighbouring villages. That said, this does not mean that Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham necessarily constituted the majority of fighters in the area. For example, the Omar bin al-Khattab Brigade was a significant local outfit in the area.

Besides, there have been valid concerns about 'reconciliation', especially the question of whether the government will actually fulfil the promises it makes, such as promises to release detainees, allow aid to enter and resolve definitively issues of military service. The concern about lack of fulfilment of promises and the role of that in the persistence of the Beit Jann pocket's rejection of 'reconciliation' became apparent when I interviewed the leader of the Hermon Regiment while the operations were ongoing to retake the Beit Jann pocket.

Further, the government did not quite have full leverage over the Beit Jann pocket, which had access to aid and goods even as the assault operations were taking place. Though it was difficult to get access to people inside the Beit Jann pocket during the assault operations, I did manage to talk to a rebel fighter who was originally from Deir Maker in the Damascus countryside. A fighter involved in the FSA group Liwa al-'Izz, he had come to the Beit Jann pocket to support the rebels there. He has since left the Beit Jann pocket bound for Deraa as per the deal that brought an end to the fight for the Beit Jann pocket. While he was there during the assault operations, he mentioned to me that there was still an open road to Beit Saber, in addition to aid being brought into the Beit Jann pocket from Israel via donkeys. For this reason, it was impossible for the Beit Jann pocket to be put under complete siege.

That Israel would send aid to the Beit Jann pocket should not come as a surprise, as Israel was likely aware that sending such aid could block prospects of a 'reconciliation' agreement for the area. The same thinking lies behind the provision of aid to localities like Jubatha al-Khashab in Quneitra that lies on the border with the Golan Heights. There were also hopes on the government's part for negotiating a 'reconciliation' for Jubatha al-Khashab along with Beit Jann last year, but to no avail.

Thus, having failed to impose a 'reconciliation', the government eventually decided to go for an assault on the Beit Jann pocket, beginning in September 2017. Contrary to pro-rebel claims, there is no evidence of a major role for Hezbollah, other Iranian-backed militias and Iranians. Although a Reuters report in late December 2017 cited an anonymous 'Western intelligence source' as supposedly confirming a major role in the operations for "Iranian-backed local militias alongside commanders from the powerful Lebanese Hezbollah Shi'i group," no indication was provided as to the substance and credibility of that source's information.

The operations were actually led by the 7th and 4th divisions of the Syrian army, though the 4th division's leading role became more pronounced over time in contrast with the 7th division. Some contingents of the Hermon Regiment played a minor auxiliary role in the operations. Quwat Dir' al-Watan, affiliated with the al-Bustan Association, also came to play a role in the fighting. There is evidence of some local Druze militia support that was provided for the assaulting forces, which will be discussed below. The only notable foreign presences in the assault were as follows:

1. The Iraqi group Liwa al-Imam al-Hussein, together with its Syrian affiliate group Katibat al-Mawt (The Death Battalion, led by Ali Mousawi) embedded in the ranks of the 4th division. Though Liwa al-Imam al-Hussein has likely received Iranian backing, its involvement with the 4th division does not mean that it was the majority or even a plurality of the 4th division's forces in the Beit Jann campaign.

2. Hayder al-Juburi serving as a commander within Quwat Dir' al-Watan, as he himself confirmed to me.

Adnan Badur, head of artillery in the 7th division. Killed in December 2017 in the Beit Jann operations.

The fighter from Liwa al-Izz who was in the Beit Jann pocket denied that Iranian-backed groups like Hezbollah and other Shi'i militias had played a role in the operations. Instead, the sectarian angle he highlighted was that of local Druze militia support for the assaulting forces, as some of the villages in the vicinity of the Beit Jann pocket are Druze. In this context, it is worth noting that Mughir al-Mir is originally a Druze village, but became devoid of its original inhabitants in 2013 when rebels captured it, a fact that rebel supporters frequently overlook.

A Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham-supporting account from the Mt. Hermon area posting in mid-December 2017: "This is one of the photos that show the participation of the hateful Druze in the battles that are taking place on the hills of Mazra'at Beit Jann, but the painful thing is that you will find alongside these people the sons of the Sunna [Sunnis] and from the sons of your locality and neighbouring localities trying to advance on the points of the mujahideen." These words are likely referring to the more minor auxiliary role of some contingents of the Hermon Regiment.

A number of fighters from both the 7th and 4th divisions are documented to have been killed during the assault on the Beit Jann pocket. For example, multiple fighters from the 7th division were killed on 12 October 2017. Similarly, one can find multiple 'martyrs' for the 4th division from the campaign. In fact, as negotiations for the Beit Jann pocket seemed to have reached a conclusion at the end of December 2017, at least five 4th division fighters from Wadi Barada were killed in a rebel ambush. One can also find instances of Quwat Dir' al-Watan 'martyrs' from the operations.

Those who claim that Hezbollah and Iran played a major or leading role in the recapture of the Beit Jann pocket neglect to note that throughout most of the duration of the operations, the focus of those two actors was on the eastern region of Syria as they aimed to help the Syrian government secure as much of Deir az-Zor province as possible while reaching and securing the town of Albukamal bordering Iraq before the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces could do so. Moreover, there is no evidence that Iran and/or Hezbollah played a role in the final negotiations over the Beit Jann pocket, as opposed to the cases of the rebel-held town of al-Zabadani and the Islamic State enclaves in west Qalamoun.

As the Hermon Regiment confirmed to me, Kinana Hawija was involved in the negotiations over the Beit Jann pocket. Ziyad al-Safadi, the leader of the Hermon Regiment, added the following: "The Hermon Regiment has a big role in the matter [of negotiations]." He noted in particular that a security coordinator for the Hermon Regiment called Abbas was attending all the negotiation sessions and keeping track of matters.

The negotiations resulted in an agreement that anyone who wished to stay, including those who needed to undergo taswiyat al-wad', could stay. However, those who rejected such an arrangement were to be transported by bus to Deraa and Idlib. Contrary to pro-rebel claims, transporting the latter by bus to Deraa and Idlib does not really amount to 'forced displacement'. Rather, many of the rebels simply decided to reject the arrangement and did not wish to stay. As outlined earlier in the article regarding the original rejection of 'reconciliation' in the Beit Jann pocket, there are reasons to reject living under government control. For instance, if you were a Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham fighter committed to the cause, would you agree to stay in Beit Jann and undergo taswiyat al-wad'? There is no other alternative for such a person but to go to other rebel-held areas, unless one thinks the government should just kill or detain all those who rejected the final agreement.

As the Liwa al-Izz fighter acknowledged to me, most of the fighters who were transported out of the Beit Jann pocket were from Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham and originally from outside Beit Jann. As for those with origins from Beit Jann, they mostly decided to stay. As for the holding force for the Beit Jann, he says that the force is to be called Fawj Souriya al-'Umm (The Motherland Syria Regiment). A source from the Hermon Regiment says it is not clear yet whether the holding force for the Beit Jann pocket will be a group affiliated with the Hermon Regiment or an independent formation. The first thing that needs to be done is taswiyat al-wad' for the rebels who have stayed.

What are the lessons of the Beit Jann affair? One of them relates to the concept of 'de-escalation.' The Beit Jann pocket was apparently supposed to be included within the de-escalation zone agreed for the wider south with Russian mediation. And yet, Syrian government forces conducted an assault that ultimately led to the recapture of the pocket. Where was Russia to put a stop to the assault? Assad and his government are sometimes thought of as mere puppets of Russia now, considering how crucial Russian intervention was to turning the tide of the war, but this depiction of a master-puppet relationship is highly questionable. One is reminded of the case of Aleppo city in late 2016. Despite talk at the time of Russian interest in preventing an all-out assault on the rebel-held parts of the city and a Russian desire to make a deal with the rebels that would supposedly prevent the need for "so many troops to hold the city," an all-out assault is what happened, culminating in the full recapture of the city by the Syrian government and its allies, with the eastern section largely left in ruins.

More generally, there is too often an assumption that the government's foreign backers are in the driving seat when it comes to conducting campaigns, and thus developments are primarily framed in terms of what is perceived as their interests. Thus, this campaign to reclaim the Beit Jann pocket is framed as another vital piece in the building of a front by Iran and Hezbollah to attack Israel. Again, such a depiction is not supported by the evidence, even though in general it is clear that Iran desires a permanent presence in Syria and wishes to harass Israel with its clients. It is not as though the Syrian government has no interests in the Mt. Hermon area, such as its general desire to reassert control over what it sees as its own country and preventing attacks emanating from the area on more loyalist communities like the Druze locality of Hadr in northern Quneitra.

A key question is: what can realistically be accomplished in Syria by various actors at this stage? There was little that could have prevented the Beit Jann pocket from coming back under government control in the long-run. The fact is that by 2017 it was an isolated rebel-held enclave largely cut off from the outside world, with a court system influenced by jihadist thinkers. The idea that preserving it would have reduced the likelihood of a future Israel-Hezbollah war is fantasy. The idea that the enclave was crucial to Israeli interests at all is also fantasy.

One article in The Times of Israel on Beit Jann by Avi Issacharoff borders on being laughable. Issacharoff claims that "the Syrians have almost completely retaken control of the border with Israel." Evidently, Issacharoff needs to work on his geography. Leaving aside Islamic State affiliate Jaysh Khalid bin al-Waleed's control of a part of the southern border area of the Golan Heights, the fact is that rebel forces still control most of Syria's border with Israel, stretching from Wadi Ta'im to Jubatha al-Khashab. It is not as though that situation has been changed by the government's reclaiming of the Beit Jann pocket, and it is unlikely to change for the near future at least. Israel, hoping to maintain what is partly considered to be a de facto buffer zone along the border, will probably seek to establish new channels of support for rebel forces in those areas as there has been talk of an end to salary payments for fighters through the operations room in Amman that has backed the highly dysfunctional Southern Front.

It is also clear that Issacharoff has not heard of the Hermon Regiment and other means that government forces have to try to pacify areas through recruiting local and Syrian manpower. It is not quite a matter of the government simply being dependent on Iran and foreign militias to hold ground. In fact, there is no need for Iran to have foreign militias stationed in Quneitra if the goal is to harass Israel on that border. There is already a well-established Iranian-backed network of Syrian Hezbollah and the Local Defence Forces, which could be used at least in part to back up Lebanon's Hezbollah in a future war with Israel regardless of the part of Israel's northern borders in which the initial hostilities take place.

In the long-run, the only realistic option for Israel is the maintenance and strengthening of deterrence on the northern borders. The deterrence thinking of course is the basis of Israeli statements that conflate the Lebanese state with Hezbollah and threaten to target the state structure in the event of a future war. The deterrence impact of articulating and emphasizing such an approach should not be underestimated.

---------------------------

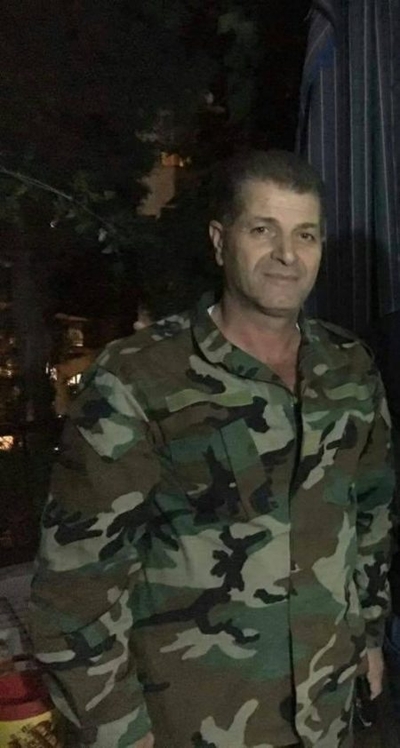

Update (3 January 2017): A reader highlights a Hezbollah fighter reported to have been killed on 16 December 2017. The fighter is described as a commander. His name was Basim Ahmad al-Khatib (al-Hajj Abu Mahdi) and he was originally from Deir Seryan in south Lebanon. He was killed in Beit Jann. Here is a description of him I found:

This death must be noted. To be clear, the article does not deny that there was any role for Hezbollah and other foreigners on the side of the government forces (two notable cases of Iraqi involvement were noted above). The point is only that their involvement does not translate to having a major role or being the driving force behind the campaign. It is also notable that the date of Abu Mahdi's death occurs very late in the Beit Jann campaign. Contrast the Beit Jann campaign with the large number of casualties for Hezbollah and other Iranian-backed forces reported in the fight for the Albukamal area (e.g. see here from mid-November 2017).