Editor’s Note: This story was originally published in March. Learn how America’s intelligence network tracked and killed the godfather of ISIS, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, on CNN’s “Declassified,” Sunday, July 3, at 10 p.m. ET/PT.

Story highlights

ISIS isn't about to file for bankruptcy -- but its balance sheet is hurting

The anti-ISIS coalition has targeted the group's financial experts

But ISIS still has one major customer for oil and gas: the Syrian regime

Outside the deserted town of al Hawl in northern Syria, a network of pipes converges on a plant with three oil storage tanks.

It’s a small facility, but for more than a year it helped ISIS’ war economy, dispensing crude to middlemen willing to risk being bombed to trade it.

ISIS fighters were forced to abandon al Hawl in November. They scrawled graffiti on the tanks and rigged booby-traps. They also left behind a bomb factory and a source of taxation: al Hawl had 3,000 inhabitants.

READ: How one strip of land could turn Syria conflict

Its retreat from al Hawl is one small example of a growing problem for the “caliphate.” Its revenues are declining as its control over populations and resources shrink.

In 2015, ISIS lost about 40% of the area it held in Iraq, as well as parts of northeastern Syria that have both good farmland and oil. Airstrikes on the oil infrastructure it controlled have further diminished the balance sheet. Some of its senior financial officials have been killed. Trading through Turkey has become much more difficult. Its cash depots have been bombed.

ISIS isn’t about to file for bankruptcy – but its balance sheet is hurting.

How come ISIS got so rich so quick?

A terror group that claims to be a state, or a “caliphate,” needs a lot of money, especially when – according to most estimates – some 4 to 5 million people live under its control.

ISIS did have a lot of money. Even before it went on its land-grab in 2014 it probably had assets worth $875 million, according to a study by the Rand Corporation. Much of that came through extortion.

It also enjoyed windfall profits in the expansionary days of 2014. These included, according to U.S. estimates, between $500 million and $1 billion seized from Iraqi bank vaults. The branch of the Central Bank in Mosul alone was said to contain more than $400 million.

READ: Syria civil war: how we got here

It also grabbed thousands of tons of military equipment left behind by fleeing Iraqi security forces, and oil wells and refineries.

The cash was rolling in. Speaking in October 2014, senior U.S. Treasury official David S. Cohen said ISIS “has amassed wealth at an unprecedented pace.”

Last year, the group captured valuable phosphate deposits near Palmyra in Syria, to add to those parts of Anbar province in Iraq which are rich in the material. Phosphates are an important ingredient in fertilizer.

A conservative estimate would be that ISIS’ cash pile and revenues amounted to at least $1.5 billion a year ago. But ISIS was also spending money – fast.

Of course, ISIS doesn’t publish accounts, so it’s tough to estimate its spending. The Iraqi government budgeted $2 billion in 2014 for the provinces which ISIS then seized. The terror group is unlikely to be spending anything like that.

Even so, ISIS still has to provide basic social services, health care, water and electricity, and maintain roads and sewage systems. It has to pay wages, even more so when the Iraqi government decided last September not to continue paying civil servants in areas under ISIS control, a loss estimated at some $170 million a month to the local economy.

What about oil?

In late 2014, ISIS-controlled oil refineries were producing about 50,000 barrels a day, worth an estimated $500 million annually. Rather than handle the sales itself, ISIS tapped into existing smuggling networks which sold some of that oil into Turkey.

The margins were slim because there were many parties involved. Still, it was a lucrative trade.

War and oil: Devastation in northern Syria

But hasn’t oil crashed?

Yes, it has, but that’s not ISIS’ biggest problem. Last autumn, the anti-ISIS coalition decided to go after the terror group’s oil infrastructure with an operation called Tidal Wave II. It began targeting oil trucks, gas-oil separation plants and oil collection points.

On one day alone last November, according to a coalition estimate, 283 oil tankers were hit near Deir Ezzour in Syria, home to about two-thirds of ISIS’ oil production. Mobile refineries have also been targeted, making it more expensive for ISIS to obtain refined products. The spare parts and expertise needed to repair infrastructure were hard to come by.

READ: ISIS faces crude reality as oil output slumps

It’s difficult to estimate current production from ISIS-controlled fields. Col. Steve Warren, spokesman for the Combined Joint Task Force in Baghdad, says it may have fallen to about 34,000 barrels a day. Another source tells CNN that at times it has fallen below 20,000 barrels per day – a drop of 60%.

Sources in northern Syria say the price per barrel in places like Hasakah – outside ISIS control – is about $20, while in ISIS-held territory it has stayed above $40. That price likely reflects shortages. There are many reports of fuel rationing, and opposition activists say the price of gas in Raqqa has risen 25%. The Financial Times reported in February that ISIS has cut its fleet of cars in Deir Ezzour from 60 to 10.

Who else is buying oil?

ISIS still has one major customer for the oil and gas it has appropriated: the Syrian regime. According to one analyst, the regime may be buying up to 20,000 barrels per day from ISIS.

But isn’t ISIS fighting against the Syrian regime?

“The two are trying to slaughter each other and they are still engaged in millions and millions of dollars of trade,” says Adam Szubin, acting under secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence at the U.S. Treasury.

ISIS’ seizure of the Palmyra area in May last year included two gas fields and a pumping station known as T3. That pushed the Syrian regime into a bargain with ISIS: “Continued flow of gas from eastern fields to regime power plants in return for payment or electricity supply,” according to Yezid Sayigh, a senior research associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

And what about taxes?

As it rampaged through Iraq and much of northern Syria in 2014, ISIS seized huge amounts of personal property. In Mosul it simply appropriated and resold the homes of those who fled and seized their bank accounts. It may also have made $100 million from the sale of antiquities, according to Iraqi officials.

And it made obscene sums from ransom payments and the sale of slaves, especially young Yazidi women. In 2014, ISIS made about $20 million from ransom payments, the U.S. Treasury estimates.

According to several studies, revenues from what is essentially looting and pillage probably made up 40% of the group’s income. But you can only confiscate a property, rob a bank or sell a hostage once.

READ: Inside the $2billion ISIS war machine

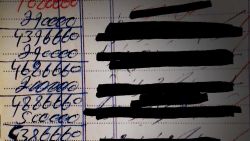

ISIS also levies heavy and various taxes on the populations under its control. Its zakat tax takes about 10% of people’s income and it’s been known to take about a tenth of the amount whenever someone withdraws cash from a bank account. There are fees for using water, electricity and cell phone services.

Ludovico Carlino, a senior analyst at IHS/Janes, says: “They charge a 20% tax on all services.”

ISIS also makes money from Christians through an Islamic tax known as jizya. “If they refuse this, they will have nothing but the sword,” ISIS announced in 2014. ‘“Apostates” have to pay a repentance fee of some $2,500, according to ISIS documents analyzed by Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi at the Middle East Forum.

Donations from the Gulf and elsewhere have helped, though not as much as with al Qaeda. International sanctions have hit donors and facilitators. ISIS has even tried – with unknown results – to exploit Bitcoin accounts to raise money overseas, even putting out an English-language guide.

So where is ISIS losing money?

Perhaps ISIS’ biggest problem now is a shrinking tax base as people have fled territory under its control, especially the professionals it needs such as doctors and engineers. ISIS documents have threatened medical professionals with having their property confiscated unless they return home.

READ: Will Saudi Arabia be sucked into Syria?

The caliphate’s economy is largely isolated from the outside world, making it more difficult to develop and sell the resources under its control – from hydro-electric power to oil, cement and wheat. That’s in part because of a major crackdown by Turkish authorities on widespread illicit trade from which ISIS benefited. ISIS also lost control of stretches of the Syria-Turkish border to Kurdish forces.

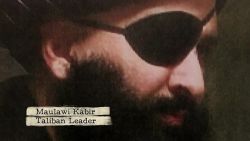

The anti-ISIS coalition has also made a priority of targeting the group’s financial experts – men like Abu Salah, described by Col. Warren as “one of the most senior and experienced members of its financial network,” who was killed last November.

That sort of expertise is not easily replicated. Other key officials have also been sanctioned, including those involved in oil.

ISIS revenues are now some $80 million a month, with half coming from taxation and confiscation, according to a recent analysis by IHS/Janes. But that may not be enough.

What’s ISIS doing about all this?

Al-Tamimi told CNN the pay cut appears to have applied only to Raqqa. But he notes other austerity measures: “Reductions in ‘perks’ for IS fighters and cracking down on ‘waste expenditure’ definitely exist,” he explained, including restricting the use of vehicles when not needed for operations.

READ:Twitter goes to war against ISIS

The squeeze may have been aggravated by a U.S. airstrike on January 11 against an ISIS depot in Mosul, which destroyed “millions” in bills, according to U.S. officials. That appears to have provoked ISIS into stepping up tax collection efforts. In Mosul and Fallujah, according to anecdotal evidence, it has also begun “selling” the right to leave to the few who can afford to do so. It costs $1,000 – $2,000.

According to some Iraqi sources, ISIS also began dispersing its cash holdings. The coalition announced last weekend that an airstrike hit an ISIS financial distribution center near Qarraya, 45 miles south of Mosul.

Where else does ISIS have problems?

As its supply lines are cut, in northern Iraq for example, ISIS has to spend more to transport fighters, weapons and supplies via more circuitous routes across the Jazeera desert.

Moving cash to buy supplies is also becoming more difficult. The U.S. Treasury Department, working with some 30 other countries and organizations, is trying to cut bank branches in ISIS-held territory in Iraq out of the international system.

But for now, ISIS is still able to access money-changers in Iraq, Turkey and Lebanon who operate outside the formal financial system.

“Don’t underestimate continued cash flow with the outside world,” Al-Tamimi told CNN. “So long as that continues, I don’t see a fatal economic collapse from within – just the standard of living getting worse and worse.”

So what’s going to happen?

ISIS is adaptive and resilient. It continues to function, with a sophisticated bureaucracy driving tax collection. Were it a typical terrorist group not focused on governing an area larger than Belgium, money might not be such a concern. But its credo is about maintaining and expanding a state.

READ: What you need to know about ISIS

And in the areas it rules, all the evidence points to rising inflation, growing shortages and an increased emphasis on force to retain control.