Amman // When two suicide bombers walked into a secret military meeting and detonated their explosive vests they killed one of the most controversial rebel commanders on Syria’s southern front, a man who was held to be central to efforts by ISIL to seize control of the south.

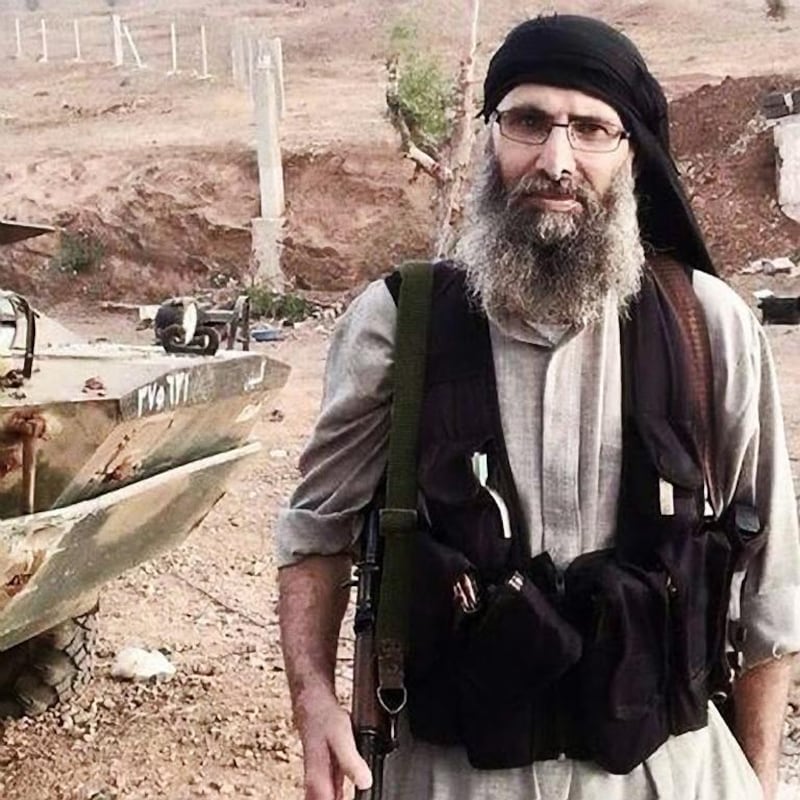

By the time a pair of Al Qaeda suicide bombers killed him, Mohammad Al Baridi – more commonly called Al Khal, or “the uncle” in Arabic – was one of the most hated and feared rebel commanders on Syria’s southern front.

Under his rule moderate rebels were assassinated, moderate clerics kidnapped, smokers arrested and thrown in public cages for weeks at a time and music banned at weddings – all part of a campaign to implement the strict interpretation of Islamic law championed by ISIL.

Al Khal’s increasingly radical views put him sharply at odds with much of the population in south-west Deraa, where, centred on the village of Jamleh, he had established an outpost of ISIL ideology.

On November 15, as news spread of his death earlier that day, there were celebrations in villages that had suffered during his reign.

Al Khal, and the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade which he led, was not always so closely tied to ISIL however. Little more than a year ago, he signed pledges to respect democracy and human rights, and even publicly thanked Israel for providing medical aid to Syrian refugees.

But within a few months of doing so he had effectively aligned himself with ISIL and was battling against his former allies.

Al Khal’s journey took him from his pre-revolution days languishing in prison to the pro-democracy movement seeking to overthrow president Bashar Al Assad and then, near the end of his life at the age of 45, into the apocalyptic worldview embraced by ISIL.

UN peacekeepers

When the Syrian uprising began, Al Khal was in jail. One opposition activist, critical of Al Khal, said he believed him to have been convicted in connection with the theft of antiquities from archaeological sites. A rebel commander from a rival faction said Al Khal had been jailed for radical Islamic tendencies. Neither claim could be confirmed.

He was freed in the opening months of the revolt, having served almost three years of his term, in an amnesty announced by president Al Assad.

Rather than just releasing political prisoners, as activists and human-rights monitors had demanded, the Syrian president freed thousands of criminals as well as members of extremist groups, who would go on to take up arms against him and help turn the peaceful uprising into the war that followed. Al Khal was one of them.

In the summer of 2012, just over a year into the revolt, Al Khal helped to found the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade, a band of rebels with a centre of influence around Jamleh, near the occupied Golan Heights and Syria’s de facto border with Israel.

It was the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade that abducted 21 UN peacekeepers on the Israel-Syria ceasefire line in March 2013, vowing to keep the Filipino soldiers hostage until the regime pulled back its troops and halted air attacks.

At a time when the Syrian opposition was still hoping to win international sympathy and enlist the assistance of the UN Security Council, the hostage-taking was a public relations disaster that backfired.

____

Al Khal: From Syrian dissident to ISIL ideologue - graphic

____

Under a barrage of criticism from Syrian activists and other rebel factions, as well as international powers backing the rebels’ cause, the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade shifted its position, saying it had not taken the UN peacekeepers hostage but was in fact protecting them from regime forces.

The peacekeepers were eventually freed unharmed but, two months later, the group abducted another four UN troops. Again, they were released unharmed but the incidents pointed to a volatility and radicalism within the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade which put them at odds with moderate rebels then dominant in the south, and which would only intensify.

Nonetheless, Al Khal’s forces, well funded and well armed, bolstered their reputation in 2013 fighting in battles alongside other rebel units, and they cooperated closely with Jabhat Al Nusra, the Al Qaeda affiliate.

Other moderate, nationalist rebel factions in southern Syria also entered into an uneasy alliance with the small but expanding Al Nusra but, in an effort to stop the Al Qaeda group becoming too powerful, they formed a coalition in October 2013, named the Revolution Leadership Council Southern Region.

The Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade joined that alliance in a move that eased but did erase fears that Al Khal was moving towards a more radical ideology.

Stockpiling arms

By this time he was increasingly seen by other rebels as under the sway of Sheikh Mohammad Sorour Zein Al Abideen, a Syrian Islamic scholar from Deraa and a former member of the Muslim Brotherhood, well known since the 1980s for anti-Shiite, anti-Iranian writings. Sheikh Sorour’s work was admired by Abu Musab Al Zarqawi, leader of Al Qaeda in Iraq until 2006.

As the Syrian uprising morphed into a war, Sheikh Sorour, described by colleagues as clever but a bully and arrogant, had been trying to gain leverage over the southern battlefield through a movement named after him and, later in 2013, through the “Sons of Houran Association”.

Rebel commanders, activists and his colleagues said Sheikh Sorour had strong connections with Qatar, where he owned property, Turkey, the Muslim Brotherhood and Al Khal. All of them were part of a network channeling money to rebel factions independently of the Military Operations Command (MOC), a centre in Amman staffed by western and Arab military officers, tasked with aiding moderate rebels.

By mid-2014, the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade had grown in strength and was stockpiling arms and cash far in excess of its MOC allocations, rebel commanders said, fuelling concern about Al Khal’s connections with the Muslim Brotherhood and possible extremist radicals based in the Gulf states who were funding the likes of Al Nusra.

“They always denied having any connection with the Muslim Brotherhood but we knew they were receiving funding from them and they became one of the most powerful Islamic factions on the southern front,” said a rebel commander. He said mid-2014 was the point at which the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade seemed to step decisively away from the moderates’ orbit into a more radical sphere.

Black flag

It was at this point that the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade changed its logo, adding a black flag commonly seen in ISIL-controlled areas. That came after footage, uploaded on YouTube in the spring, showing Al Kahl being serenaded by an ISIL song. ISIL music was added to Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade propaganda videos at about this time.

There were also signs that Al Khal’s forces were increasingly staying out of battles with the regime and conserving their strength – a strategy perfected by ISIL in its strongholds in eastern Syria. Some members of the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade, unhappy with the direction it was heading, began to leave, joining other, moderate groups. But Al Khal, flush with cash and weapons, continued to attract recruits.

Although Syria’s Muslim Brotherhood was part of the mainstream opposition, it had come in for significant criticism from anti-Assad circles, accused of duplicity and of trying to monopolise the broad struggle against the Syrian president. Regional concern, particularly in the Gulf states, over the Muslim Brotherhood’s reach was also on the rise as it ascended to power in Egypt.

Sheikh Sorour was detained by Jordanian security services in March 2014 over his backing for radical factions in southern Syria and amid spreading concern in Amman that he, and his allies, were trying to destabilise the southern front.

As Nusra and other extremist groups continued to expand their power in southern Syria, moderates sought to reassert themselves and the principles for which they were fighting. In June 2014 rebel brigades signed a public pledge to respect democracy and dignity.

Al Khal committed to that pledge but it failed to convince the MOC that he was genuinely part of the moderate alliance. In June, as ISIL dramatically seized control of Mosul in neighbouring Iraq, the MOC reassessed the groups it was backing and decided to halt funding to the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade. That decision was driven more by concern over the Muslim Brotherhood’s influence on Al Khal than the blossoming but not yet concrete ISIL connection, according to rebel commanders familiar with the move.

ISIL law

Pulling the plug on Al Khal was controversial in the MOC. Jordan, which had by then deported Sheikh Sorour, argued for continued funding, on the grounds that, as patrons, the MOC would retain some influence over the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade and be positioned to steer it away from the radical fringe. The UAE and Gulf States, more alarmed by the prospect of growing Muslim Brotherhood power, had argued in favour of stopping the cash flow.

Cut off from the MOC, the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade began to even more strongly echo the practices of ISIL, including taking openly hostile stances towards other rebel factions and accusing them of being un-Islamic; an extremely serious charge to make and tantamount to a declaration of war against them.

Three months after halting funds to Al Khal, however, the MOC reopened the flow. Rebels familiar with MOC operations said it transferred US$50,000 (Dh183,600) to the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade in September, half the amount Al Khal had requested for his troops, thought to number more than 650 at the time.

This reopening of the funding pipeline was part of a last-ditch effort to bring Al Khal back into the moderate fold and to bolster the southern front against ISIL infiltration. It coincided with a statement, which appeared to have been issued by ISIL, vowing it would take over southern Syria in “a matter of days”.

The creation of a unified court system, the Dar Al Adel, with authority over all armed factions, was central to that anti-ISIL effort. The Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade was part of the painstaking negotiations but, in the end, refused to endorse the court, which was based on a pragmatic mixture of tribal, customary and Islamic law.

Instead, Al Khal took an openly hostile stance to the Dar Al Adel, pronouncing it un-Islamic, and the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade established its own court, which soon began enforcing rules similar to those used by ISIL in areas under its control.

Also around this time, Al Khal refused to make a public declaration of independence from the Muslim Brotherhood, something the MOC had demanded in exchange for continued support. As a result the MOC halted funding once again, for the final time. Despite that, the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade took part in November’s broad offensive when a rebel alliance routed regime forces in Nawa.

Echoing rhetoric

It was the last major act of cooperation between the group and other, mainstream, rebel units

Within a month, the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade was at war with Al Nusra, and the Dar Al Adel had launched an investigation into Al Khal’s alleged links with ISIL. The court authorities later said it had received confirmation from Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade members that the group had pledged allegiance to, and received funding from, ISIL.

At this point Al Khal's affiliation with ISIL was "so obvious that it does not really make sense now to speak of the group as secretly pro-Islamic State", wrote Syria analyst Aymenn Jawad Al Tamimi in a detailed history of the Yarmouk Martyrs' Brigade published on the Syria Comment website.

Since the summer of 2014, Al Nusra had been conducting an intelligence operation within its own ranks, led by Abu Maria Al Qahtani, arresting dozens of people it believed to be ISIL loyalists trying to subvert it from within or defect to the more radical group.

Al Qahtani, an Iraqi, fought against ISIL in Deir Ezzor, in eastern Syria. When his forces in the east were defeated, he moved to the southern front, reinforcing Nusra there.

Considered one of the more pragmatic elements of the Al Qaeda franchise, Al Qahtani led Al Nusra’s anti-ISIL efforts in the south and came in for particular vilification from the extremist group, which insultingly nicknamed him “Al Hariri”.

Research by Aymenn Al Tamimi showed the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade shared ISIL’s hatred of Al Qahtani and copied its rhetoric, also referring to him as “Al Hariri” and accusing him of “treachery” and “conspiracy” for his opposition to the Jihad Army, another faction in the south tied to ISIL and Al Khal.

Despite blatantly adopting ISIL’s logo as part of its own, sharing songs and echoing its rhetoric, the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade never publicly acknowledged affiliation to ISIL and Al Khal denied being aligned with the group up until his death.

Defections

Fighting between Al Nusra and both the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade and the Jihad Army continued intermittently, although often with deadly intensity, from December 2014 throughout 2015. Moderate factions, who had little affection for Nusra or Al Khal, stayed on the fringes of the conflict but were, inevitably, caught up in it at times.

Some 30 moderate opposition commanders were assassinated by Al Khal’s hit squads, according to moderate rebels – as the struggle peaked in October and November.

But Al Nusra had slowly gained the upper the hand, sparking defections among Al Khal’s men, and on November 15 it dispatched a unit to attack a meeting attended by Al Khal and other senior members of the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade in its stronghold, the village of Jamleh.

The attackers included two suicide bombers who blew themselves up, killing Al Khal and his formidable deputy, Abu Abdullah Al Jaouny, one of the men held to be the real driving force in the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigades. In the weeks after the attack, even more of Al Khal’s followers left the group, according to moderate rebel commanders.

But the group set up by Al Khal, and steered by him into the ISIL fold, fights on. It is now led by Abu Obaida Qahtan, who has been reinforcing his troops and, according to a moderate field commander in the area close to Jamleh, offering five times the $50 monthly salaries paid to many ordinary rebel fighters in order to attract recruits. For fighters struggling to support their families, such payouts can be hard to resist.

Moderate rebels saw the killing of Al Khal as a setback for ISIL in the south, but not an end to its efforts to gain supremacy there. There is certainly no sign that Abu Obaida Qahtan will attempt to bring the Yarmouk Martyrs’ Brigade back to the side of the moderates. Although weakened with perhaps 250 men left fighting on his side, according to moderate rebel commanders, Abu Obaida Qahtan is considered even more of a radical, and more pro-ISIL than Al Khal.

foreign.desk@thenational.ae

* Phil Sands contributed from Boston, USA